Críticas (538)

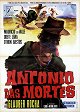

Antonio Das Mortes (1969)

The era of cangaceiros - the bandits of the sertao, the arid northeast of Brazil - has ended. It not ending because it has already ended: in the film, the characters move deliberately as if lifeless (the burned-out Antonio, whose raison d'être perished by his own hand; Coirana, who is merely a follower of a dead bandit tradition and in the film only literally dies from a certain point onwards; the blind old landowner, foolishly defending his property, a typical character of perverse dehumanizing greed against the green of life, etc.). Rocha can better build the brand of his work in this way: the intertwining of reality and myth, characters mythologizing themselves, the transformation of real misery into a mythical reflection, etc. Moreover, the intertwining of counterpoints is repeated in other narrative elements: in the mise-en-scène, for example, when Antonio and the bandit Coirana meet (a meeting so quick compared to Black God, White Devil..., where we waited for it the whole film), and in which the characters unexpectedly blend in one long shot, until suddenly they face each other, but also in the scenes when Antonio (dressed in early 20th-century clothing) stands amidst modern car traffic. Cars speeding by, indifferent to the characters of the movie. This is the main counterpoint and the main message of the film: the myth of cangaceiros is dead, times have changed; the myth of yesterday is not an inspiration, but precisely a juxtaposition with today. The struggle of today only comes when the last myth of yesterday dies and becomes just a memory, and only then can it strengthen those who are going in the same direction as he once did. This is the engaged message of the film, personified in the character of the "Professor": just like Antonio, he joins the side of the people only after Coirana's death. So, what does the awakening of the mercenary Antonio mean? In my opinion, it is a clear parallel to the situation in Brazil at that time and the rise and consolidation of the military junta in the late 1960s: Can't Antonio's awakening (the soldier) and his alignment with the Professor (Rocha's left-wing intellectual type) against the blind landowner serve as an appeal to the army to join the side of Brazilians and turn against the isolated bourgeois/landowning elite?

Totò che visse due volte (1998)

A spiritual and more humorous successor to films like One Man and His Pig by Zéno and Begotten by Merhige - a total desacralization and destruction of all fantasies about a higher existence of human life, concretized as religion as with Zéno, which grows here as well as there from the most animalistic foundation of a human being as an animal and is nothing more. Masturbation as a principle of life: the masturbation of a pubescent panicking in anticipation of sex with a woman and fantasizing about how great it will be, just like adults always wait for the arrival of love, the messiah... The authors stretch this masturbation moment, turning adult actors into pubescent figures, dreaming of big breasts (maybe those from Fellini's Amarcord?)... Above all, through the absence of any real women (except for desexualized old women who, moreover, are also played by male actors during the film /perhaps without exception?/), they show how a woman and the Virgin Mary are only the product of a "pubescent" male brain. Unlike the two aforementioned films, which, even from the depths of their materialism, evoke a feeling of tragedy, horror, or sadness in the viewer about the human condition, "Totò..." (of course, the name of the famous Italian comedian) with its comedy prevents any feeling of nobility and is therefore much more unbearable than, for example, the unbearably brutal shots of a human reduced to a piece of meat in Begotten. However, the film does offer beautiful cinematography, it must be said - yes, that is also the only thing that remains when you discard the nonsense of all the content...

L'Amour fou (1969)

Unlike other experimental films of the time, the film tackles both the techniques of film and theater but paradoxically does not directly address itself, meaning the current plot, but only the medium of film (or maybe just television? In any case, something to do with the camera...) and drama. The medium of film is approached in a slightly metafictional spirit of a television crew that introduces techniques of cinéma-vérité into the entire film, which on the one hand serves as a humorous counterpoint to the linguistically pompous Racine classicism, and on the other hand, complements the simplicity of the mise-en-scène of that theater within a theater. Above all, it raises the question of whether Rivette is using it as a counterpoint or as a complement to his attempt to capture the disintegration of mad love – should the viewer follow a faithful depiction of the plot (Ogier-Kalfon), or should something always escape them? Thus, should we even try to understand the psychology of the characters, especially Ogier, or should we consider psychology as definitively ungraspable because it is still in the process of being formed? And what is this stage if not a theater rehearsal? The thematization of drama in Rivette's works is an apotheosis of theater, even at the expense of film. A nice comparison is presented: Ogier=content, Kalfon=form. The same can be translated as drama=content, film=form. Not only are the relationships homologous to a theater rehearsal (where, for example, Ogier quotes and transforms the same Racine at home, etc.) and thus the driving force of the film, but also in this thematization, theater is the primary instance: the film comes to shoot the creation of the drama, and it only lives while the drama tries to live (that is, to move towards perfection through repetition, even if it should only be a horizon), or as long as Ogier and her madness try to achieve the impossible: love.

Optical Surgery (1987)

Miron, as an admirer of Sharits, has a sense of psychedelia (and for experimental film itself...), and his films are a celebration of the most sensual and meaningful element of cinema, which moves from discourse to its materiality and back. The use of found footage, especially various vintage (considered obscene from today's perspective of the 50s and 60s) scientific, educational, and advertising materials, further emphasizes this shift, when the words and images that appear as self-contained authoritative and meaningful formations begin to reveal their unconscious essence: the pure joy of movement, colors, and rhythm, which gives each image, film, or science its effectiveness. F. Miron's joyful science, as the heir of structural film, a celluloid fetishist, and a descendant of Sharits' films in their psychedelic aspect of the 60s, summarized in the words from Miron's film The Evil Surprise by Timothy Leary, who is forgotten today: "any reality is an opinion." And Miron's opinion is that we should see the material from which reality is composed and which fascinates us for its own sake.

Spacy (1981)

A poem about self-referentiality of form, tautology of image, and multiple reflections of mirrors, which only simulate depth. Replace the surface of the mirror with the surface of a film window, and you have Takashi Ito, who will constantly reveal the impenetrability of the medium and its own powerlessness before the materiality of space and objects: the viewer deriving pleasure from the repetitive game of the medium with itself becomes a helpless captive of its spectacle, caught in the nonsensical (because it does not lead anywhere, all movement in the author's films is circular and therefore purposeless) delight in the visual power of the image, to the extent that he forgets to see that his powerlessness is merely a reversed reflection of the impotence of the medium itself (in Ito's works, the "camera" always collides with some walls without ever penetrating them, as in "Box," or it only penetrates them in an illusionary way, as in The Mummy's Dream, only to relocate to the beginning of another wall...). The impotence of the medium, which will never reveal anything, explain anything, or penetrate anything: the only thing it offers is the oblivion of this bare fact through the power of spectacle and infinite postponement (until the end credits) in the form of... what? The form of form, of course. Thus: a certain formal structure, which had primacy over content, becomes itself the content for another form on the next level. This is most evident at the end of "Wall". And if Ito were not smart enough not to attempt it (because then the sobering would come), he could lead this escalation of forms to infinity...

Thunder (1982)

Takashi Ito is the video poet of alienation in hyperreality, the true "horror" of today. The real face of a girl is hidden from view - and when the viewer finally sees her, they realize in hindsight that it was only on the surface of artificial media. This is because this constant game of concealing and revealing the movement of the girl's face, this game of secrecy and its revelation, promise, and fulfillment, is just a phantasm, a simulacrum of a television or computer screen, on which our desire is estranged today. The person seeking the true face, in a futile frantic search, transforms into an immaterial, abstract discharge, mindlessly and futilely circling in the "desert of the Real," perpetually orbiting the girl's image. Ito will later use the motif of an electric discharge as a metaphor for the modern human in the thematically and methodically related Ghost (but only in Thunder can we observe and understand its genesis), and Ghost adds another layer to the relationship between reality, desire, and image: the male protagonist, and not just an object of his desire as presented here, is trapped by the screen, fragmenting him into a series of partial objects (eyes, hands, ...). This is because only the constant circulation around partial objects, promises, and repeating loops (compare computer games and their jerky repeating loops of programmed actions), is left to the viewer before Ito reveals in the end that the girl's face is unknowable in reality. God used to be sought in it, but Ito's films show (notice the gradual purification of the mise-en-scène, culminating in the bare walls of a concrete building serving only for the projection of the girl's image) that bare emptiness is found where we looked... for anything and everything.

O Rei das Rosas (1986)

Schroeter creates a dreamlike opera about desire and death, with a structure based on the pleasure from pompous images of a Baroque style and the intermingling of characters' ideas with reality. Although rather than reality existing within the film at all, the film itself seems to be merely an unraveling of its characters' fantasies. Schroeter thus put fantasy in the foreground over the story, much like "in the work of Georges de La Tour, space does not exist. His characters emerge from a black background." Similarly, all of Schroeter's characters emerge from the dark depths of unconscious and conscious desires. Additionally, they seem to appear directly from the depths of other characters: the son is merely the mother's desire, and the lover seems to exist only through and for the son... also, the dark and occasionally extravagant stylization naturally refers to Early Baroque painting in terms of aesthetics - the camera captures scenes of summer nights with twilights reminiscent of Caravaggio. In fact, Caravaggio's homosexually charged depiction of saints and mythical figures of boys and men not only offers a parallel to explicit and typical minority issues in Schroeter's work but also represents one of the themes of the film, i.e., the entangling of religious symbols with their sexual connotations.

Box (1982)

What happens when a frame appears in the middle of reality? A surface is created. And what does the frame frame? Or rather, what does it add to reality? Absolutely nothing. It's just a square/rectangle that doesn't actually change anything. And yet it changes everything completely because, from that moment on, the viewer believes that the framing carries some MEANING. That there is SOMETHING hidden behind the surface, created by the frame and the image it creates. What is in the frame of the picture must mean something, if it is worthy of being displayed; the world is rich and there is always something to discover in it, when there is something that is BEYOND the frame and still eludes us, and we sense that it will be the real thing. /// Reality is three-dimensional. Box - three-dimensional object. Film can uncover the truth; it can be three-dimensional. Takashi Ito replies that that’s nothing but shit: his box is only a six-sided surface. All things about themselves and hidden essences, meaning concealed inside reality and waiting for our discovery, collide with the walls of the surfaces of this cube. This is because that hidden meaning was all along just an effect of the frame/surface itself and our illusion (some call it life), that something is hidden behind this surface. It is because Ito's box is empty from the beginning. Just like in Spacy, the viewer only watches a closed game of the surface itself, behind which there is NOTHING, only our fantasy that we will someday break through that wall. When I believe again that life has meaning, go ahead and punch me the way Takashi Ito just did.

São Paulo, Sociedade Anônima (1965)

Cinema novo (certainly also due to the fact that it was influenced by its European models, while Europe already had its burned-out bourgeoisie) embarked on a critique of the alienation of the average well-off person, who seemingly lacks nothing, at the same time as it arose in Brazil (although poverty still persists in Brazil and not everyone lives like the main hero). It is something akin to European critical realism in the 19th century, but with a camera and not so much realism, because the film relies on unconventional (although not particularly experimental, it must be noted) narrative work. Aside from the 1960s motif of bitterness in the protagonist's class, and youthful resistance to the necessity of assimilating into a society that he disdains, it is most interesting to observe how, due to the synchronous narration of the three types of relationships with three women, the main character never escapes his bitterness from the beginning of the film (it is not gradually built up) and how every apparent calming and fulfillment of a relationship is just a false interlude between various failures, an interlude that the viewer always learns has already occurred and the present belongs only to dissatisfied emptiness. The present - as well as the ending... yet the most interesting thing is to observe the camera work of Ricardo Aronovich. Just take a look at who he filmed for in later years.

Unsichtbare Gegner (1977)

The woman and her madness come from not merging with the image of the world that surrounds her, and apart from understandable and explicit feminist criticism (the idea that Valie Export would make a film in the style of Ed Wood!), the most interesting thing is how it grasps (even autobiographically) art as criticism and an artistic tool in the mechanism of the film itself. That is because the schizophrenia of the main character arises precisely from the splitting of reality into its one-dimensional "normal" component and the (re)duplicated copy, visible only through the lens of a camera or the angle of engaged art. In addition, the main character, applying her artistic practices to herself (and thus causing schizophrenia), is increasingly under the control of "invisible adversaries" who progressively replace "normal" people and situations themselves because the main character/artist turns away from the normal perception of the world in favor of the artistic, and it is only through this that she is able to see that "invisible" (but determining) component. Therefore, Export logically intertwines the film with sequences that stand on their own, without a necessary connection to the overall story.