Críticas (538)

A Falecida (1965)

How to liberate the suffering when suffering is the means to fulfill their desires – Hirszman performs a cut into the morality of the Brazilian petite bourgeoisie, in which the struggle of the favelas and poverty against the external/class enemy is replaced by the internal struggle of the declining petit bourgeois against themselves. The wife, representing a model hysterical structure in which there is a constant shifting of her own life dissatisfaction onto new objects, finds her complement in the husband's inability not only to find work but to not even look for work: any real resistance á la traditional cinema novo is inconceivable for the protagonists who enjoy their own satisfaction in privacy. As the film (and probably its literary source) brilliantly shows, the symbolic and intellectual horizon of the protagonists does not go beyond the framework of their class, which lacks the abundance of the upper society and the radicalism of the low classes' poverty, and therefore they need to never have too little but also not too much - the closer that power is, the more internal sabotage occurs (abandoning a lover, squandering easily earned money, etc.). The cornerstone of the work's construction is that it is precisely this view of their class, which regulates and motivates the actions of the main protagonists, that is visibly personified in the character of Glorinha, a wealthier relative – her omnipresence in the field of the protagonists' internal motivation is balanced precisely by her factual absence.

Here East (2018)

An unpaneled window into the soul of residents, a voyeuristic view of the camera into the apartment of a contemporary Heideggerian stay, from which we see nothing more than everything. This is because maybe there is nothing behind the blind angle of the wall; and maybe everything is there, just hidden behind the limit of the camera. Everything will only be there when we want to dream the dream of an evening serenade, of a terrace against the backdrop of a sunset, of peace after a day at work. For those who believe that a camera is a tool of knowledge as powerful as a pneumatic hammer, the camera reveals that the orthogonal world of a residential building, the window frame of a life's image and a television masterpiece canvas, shining into the darkness with colors a million times more saturated than the reddest of sunsets, cannot do without the isomorphism of all elements, whose necessary visual counterpoint and at the same time ideological complement shall be the absence of life outside the delimited zone of interest. A square and a rectangle (the basic building block of the life's prison of contemporary humanity) teeming with empty life against empty streets and a sky without humans.

Clímax (2018)

Almost every other better film critic has outlined a quick, more or less modest parallel between Bosch's depiction of Hell from the triptych "The Garden of Earthly Delights" and the second part of Noé's film, i.e., the "horror" part. It would be a mistake, as every other critic does, to separate the first part (before things go wrong) and the second part of the film, just as it is impossible to separate the parts of the triptych. Here, we can rely on the idea that was expressed in Jean Eustache's film about Bosch's Hell: "I really feel that it is in the third painting, in the description of Hell, where Bosch finally lets himself go. He lets himself be carried away by the description of pleasure, senseless and complete. This pleasure is so complete that even its consciousness is not present." If the relationship between painful pleasure and the attractiveness of terror is only a conscious contradiction, while at the level of the unconscious, it is the desired goal of the death urge, towards which we willingly walk with joyful tears of horror immediately after LSD disables our social inhibitors, it is a possibility that Noé does not precisely examine - he only shows it. That is his classic position for me: a mixture of shallowness and a desire for depth. Fortunately, we already know that contradictions are not mutually exclusive, but collide with each other, so it is not possible to give up on Noé's work for such reasons, just as Bosch also had a troubled relationship with perspective and, therefore, with the depth of the field; criticizing Noé for shallowness would be nothing more than bourgeois attachment to the conscious sphere of film.

Vozes Distantes, Vidas Suspensas (1988)

The film resembles a family photo album: the central composition of the camera, like the naïve art of the domestic Daguerre family, captures family gatherings and family milestones for eternity. From these, a slightly musty wind blows onto the viewer from the places of eternity, carrying the bittersweet trills of the Orphean lyre of British commoners, into which everyone immerses themselves as if into death, which they are already living. If the characters try to avoid ending up like their parents and grandparents but still become what they never wanted to be, is death, which we all in vain try to avoid and which robs us of ourselves, the best analogy for a family photograph and a popular tune? And if Davies' film consists of these two main building blocks, isn't the keystone of the entire film construction the fact that the actual death of the tyrannical paternal figure only creates a space for the lasting influence of death spread across the lives of all his children and his children's children... until we arrive at the beginning when the mythical father, here somewhere in the bushes of Albion, died and as an echo of his death, the mourning of his children still resonates in the form of national songs.

O Palácio dos Anjos (1970)

Khouri once again critically examines his society, this time with a fitting aesthetic doubling of privileged detailed camera shots focusing on the gaze of the studied female characters, as if announcing that the perspective on this society will come from the viewpoint of women. This is a shift, as correctly stated in the article here (http://www.aescotilha.com.br/cinema-tv/central-de-cinema/o-palacio-dos-anjos-walter-hugo-khouri-critica/), compared to his most famous film Eros (1964), which is told from a male perspective. That is why the film may be disappointing for viewers who expect women to be portrayed as sexual objects because, despite the undeniable beauty of all the main characters and the sweetly reminiscent soap opera colors, this is a film as cold as the gaze of Geneviève Grad, in which the siren of escaping dreams always faintly echoes in the background music. In our society, predestination teaches us that luxury and money bring victory only to those who completely sell their soul, and this kind of Faustian gesture is played out here - and it is still played today and here.

Baxter, Vera Baxter (1977)

There was a time when the diegetic name, like an incantation, unleashed an unstoppable flow of non-diegetic music that sewed together every cinematic frame in a strip, and that time was during a period when avant-garde cinema did not trust linearity very much: the obsession with musical loops denies the directionality of the sound strip just as the typically Durasian windless-ness of a human ship stranded on an Atlantic shoal is all the more tossed by the winds of internal oceans, whose waves can sometimes hide the calm of depths already indifferent to everything or at other times, the calm surface masks underwater currents, but there is always a dialectic of surface and depth, which are never mutually visible at the same time, and because of that, the whirlwind of emotions, memories, and desires moves in cyclical self-transformations, attempting to unite that which cannot be united.

A Lua na Valeta (1983)

"All eternal bliss desires failed things because all bliss desires itself, and thus it also desires the sorrow of the heart." Indeed, the most noble aim of art is the mutual adequacy of content and form, which is not achieved here 100%, but undoubtedly it is at least about a strong mutual interconnection: the story of a person (specifically and generally), who always finds a way to boycott their own happiness, finds support in the "neo-baroque" form of cinema du look, which is based on the search and ideally also on finding the point at which the chosen expressive means at its peak boycotts itself. The human desire to achieve the object of desire is always self-sabotaged, whether after its fulfillment or just before it, as in this case, which always proves again that true bliss is not derived from success, but from one's eternally renewed suffering. It is precisely in this elusive difference (= the absent present lost sister) between conscious desire (= Kinski) and unconscious bliss (= Abril) that the film form (= melodrama, advertisement) settles. What else but these genres, which want to impose on people their false plenitude, false closure, and false success, can demonstrate on themselves the inherent self-destruction of human desire? Where the main protagonist reaches the edge of their desire and retreats, we find the kitschy scheme, as if fallen out of an advertisement for romantic fiction, collides head-on with its own limit and turns into its own opposite (from romantic fiction we get to the urine-soaked drunk through the red blood on the sidewalk, etc., etc.).

A Montanha Sagrada (1973)

The film, which confesses to itself, changes its ending into a beginning and thus becomes a myth that both depicts and creates: both are based on the retroactive self-forgetting of humanity, which lies in one thing - forgetting the fiction we create and mistaking it for reality, into which we are born. Fictions and myths are born only in retrospect, today gives birth to the Christs we dream of, and therefore the final metafictional catharsis opens two initiatory paths for the viewer: firstly, not to forget that the film is never more than just a game and a shadow, even if the bourgeoisie ideology of "Realism" has been presenting its shadow play as a window into reality for two hundred years; but above all, not to forget that the end of this film is the beginning of the history we live, just as every society retrospectively manufactures myths of its own beginnings, which console it on the path to the grave. Collective unconsciousness is mirrored here precisely in nothing else, somewhat paradoxically for Jung’s textbook, with whom Jodorowsky's relationship later deservedly withered, than in the fact that it is constantly changing in history, and if there is anything to be seen in its repellent attraction, it is only that desire simultaneously attracts and frightens and hurts even when it satisfies: Joseph de Maistre's quote "every country has the government it deserves" can be changed to "every society has the rulers it longs for," but only with the knowledge that people's unconsciousness forces them to forget that behind their desire for justice, nobility, and life, there is the obscenity of pure power, excrement, and death, which have always inevitably stood at its birth. And thus, they have them, from the beginning of all ages every moment, even on December 6, 2020, on any given day…

Estranho Encontro (1958)

Khouri is shown here as a talented author who perfectly understands the medium and genre and knows how to use it for his purposes. Just as he later managed to crush the bourgeoisie with its own weapon - the Antonioni self-reflective mirror of empty nights and empty souls - he demonstrates here with subtle play with the film genre a bear service to conventional Hollywood drama, almost on the edge of parody. Hitchcock grasped, understood, and surpassed. Partial spoilers follow: the demonic character of the main antagonist, whose terrifying and alluring nature was heightened by the mise-en-scène game of delaying the reveal of her face, turns out to be a paper tiger after the cataclysmic revelation - the revelation of banality does not lead to any revelation of hidden evil behind a normal mask, thus intensifying its scariness ("even a normal person can tear us apart in the shower"), but rather the hidden evil is revealed as a demonstration of the principle "fear has big eyes" (like the exposed fixed gaze of the main protagonist, see also the film poster), thus revealing the typical process of bourgeois film audience psychology. The mysterious evil is revealed as a helpless neurotic. Similarly, where the viewer of conventional 1950s films expects the final shot of the happy couple around whom the whole melodramatic plot revolves, they find the exact opposite: instead of a happy ending (gain) with a man and a woman who have been waiting for each other and have become terrifying representatives of phantasmagorical happiness of Hollywood's alias capitalist-surrealist superhumans, they see the loss (sorrow) of a humanized character who, all the way up to the climax of the film, was associated with danger through the typical means of film symbolism (again emphasized in the mise-en-scène, for example, by wearing the same coat in the happy ending scene that previously symbolized danger). Moreover, the eyes of the main protagonist say much more than they would like to. And it could continue: Khouri's subversion of conventional genre meanings makes this film a unique foreshadowing of the fact that after understanding the rules of the game, every game is revealed as empty: including the film, including life.

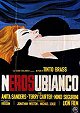

Nerosubianco (1969)

Black and white, fantasy versus reality mixed in pop-art shades of advertising print colors for sexual satisfaction, which blurs their ontological and narratively film-like distinction into an infinitely unraveling loop of motion of the offset printing cylinder, which takes on shapes, situations, and images from the collective matrix of dreams and reprints them into the unconsciousness of the main protagonist, who instead of delving into the depths of her own unique satisfaction, wanders in the whirlpool of consumer crowds; the individual's imagination is captivated by the idea of others, who are either an obstacle to the protagonist’s gratification (the paranoid function of the camera by Tinto Brass, the multiplication of gazes, the menacing presence of uninvolved individuals) or an exaggerated key to the Desire station; however, since T. Williams' time, we know that the final destination of this tram is the cemetery. Therefore, after getting too close to the object of her desire, the protagonist alternates between the danger of a black man's skeleton and the bourgeois safety of her white symmetrical husband.