Críticas (863)

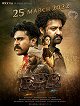

RRR (2022)

While Jákl went looking for success in the Bohemian Basin with a reimagined Jan Žižka (which he probably would make today in a completely different way than as a copy of Braveheart), Indian hitmaker S.S. Rajamouli showed how to update national heroes for the masses of the new millennium. Following the example of comic-book crossovers, he transformed two historical figures into fictional muscular characters in a hyper-bombastic bromance, where heavyweight soap-opera melodrama is interspersed with spectacular action scenes executed with unbridled creativity and goofy ambition unbound from the confines of dull realism.

Dr. Goldfoot and the Girl Bombs (1966)

Mario Bava searches for the vein of gold at the very bottom of plebeian humour. Immersed in the era of blockbusters, we forget that earlier sequels were usually no bigger, costlier or more bombastic than the initial hit. This was true particularly in the area of trash productions, which was dominated by the American International Pictures studio, where the rule was that sequels were supposed to be quickly churned-out appendixes to box-office hits with the aim of squeezing the last drop from the brand. This is clearly illustrated by the second Dr. Goldfoot movie, which was slapped together by Mario Bava in Italian studios. What remains from the first instalment is the Bondian villain played by Vincent Price and his artificial beauties. Otherwise, everything is obviously cheaper, more futile and more insipid. Even Price is visibly annoyed and we would search in vain for the self-indulgent verve with which Price played the same role a year earlier. In can be seen in the film that Bava shot a lot of material that was subsequently tamed by the editors. The film’s handful of flashes of inventiveness, especially the balloon sequence (which seems like a direct inspiration for the creators of Dinner for Adele), are unfortunately overshadowed by the crude Italian humour, most disturbingly personified by a pair of domestic comedians mugging for the camera.

Dr. Goldfoot and the Bikini Machine (1965)

Under the leadership of veteran producers Samuel Z. Arkoff and James H. Nicholson, American International Pictures was a shark in the fishpond of American trash flicks. While other trash production companies collapsed over the decades due to the changing moods of the audience, AIP kept going and never ceased to try new things. The Dr. Goldfoot franchise came about when the studio was on the hunt for lucrative new concepts as previous fads, particularly Poe adaptations, were in their death throes. At that time, AIP tried to go the route of modestly lascivious, madcap comedies, in which they stylishly recycled the studio’s older hits. Pajama Party (1964), for example, builds on youth exploitation flicks and How to Stuff a Wild Bikini (1965) is reminiscent of earlier biker movies. The first Dr. Goldfoot both recalls the virtues of these beach farces and simultaneously exploits the Poe tradition, while also making fun of its rival, the newly established Bond franchise. The result is a playful farce with a magnificently overacting Vincent Price as a Bond-calibre evil scientist who creates luscious artificial beauties whose task is to enchant the rich and deprive them of their fortunes. Following the example of the above-mentioned films, there is also a mix of insipid attractions with heavy-duty slapstick comedy in which the older, fading star oversees the silliness of the younger actors. But unlike the sad sight of Buster Keaton in the previous films, Vincent Price throws himself into his role with tremendous verve, thanks to which the first Dr. Goldfoot is a wonderfully entertaining farce.

Batman Regressa (1992)

This is what it’s like when, after nearly three decades, you look back at a film that made an impression on you in your early teens and you find it surprisingly bizarre, deranged, perverse, oversexed, unique and beautiful. In today’s era of thoroughly planned-out blockbusters that are meticulously controlled for the sake of corporate image despite being marketed as tremendously innovative and original, Burton’s second Batman comes across as a magnificently anti-system achievement. It’s not only that Burton ignores the comic-book canon obsessively guarded by fans, which he quite consciously doesn’t care about. Equipped with a generous budget and creative control, he spins a romantically sick and sleazily beautiful antithesis of various American myths, from the political system to superheroes to Christmas. Batman Returns is like a snowman turned upside down, its bottom revealing the hidden ugly underbelly of the kitschy idyll. With almost operatic sweep, Burton conducts phantasmagorically stylized scenes combining gothic monumentality with the deviance of expressionism. In this world, he lets the circus freaks run riot, as the heroes and villains differ only in that, for various reasons, they cannot give vent to their inner desires. Spandex has been replaced with latex and the masks and costumes do not look like tough armour, but rather like fetishistic outfits in which the characters vainly try to hide their childhood traumas and adult perversions, obsessions and dreams of boundless power from the outside world. However, Burton’s Batman movie isn’t pompously dark and serious like those of the new millennium. In his grotesque vision, bleakness is just as essential as the classic comic-book unseriousness of the slapstick dimension. Like the world depicted in the film, its logic, violence and the antiheroes themselves are cunning, theatrical and childishly spiteful, but also full of grief, pain and a naïve longing for something better. Like all good Christmas movies, this one is about family, belonging and resting in the arms of loved ones. But with the difference that the heroes here can only dream about that.

Ski to the Max (2001)

Bogner crowned his creative career with the last goal that he could set for himself as a cinematographer. He treated himself to the luxury and the challenge of the IMAX format. In the end, it doesn’t matter much that a lot of this film’s sequences are just rehashes of previously executed feats (slow-motion powder runs and a bobsled run), because the completely new format and its guaranteed dimension bring sufficient updating and enhancement of the proven attractions. In terms of the screenplay, Ski to the Max shows Bogner at his most unrestrained. The narrative is even more elementary than in White Magic. Specifically, the individual music-video-style sequences comprising money shots of adrenaline sports are connected by a storyline in which a nameless athlete is stuck in a car at an intersection, waiting for the light to change, his mind drifting freely into various fantasies spurred by the vague details around him. This overarching premise could be labelled as a mere crutch or a sort of additional vague connective tissue. But the same, almost Dadaistically unhinged and anti-conventionally random logic is also exhibited in the individual music-video-style action sequences, which were obviously developed precisely according to where Bogner let his thoughts wander when layering the individual ideas. Indeed, the narrative does not aspire to any conventionally causal framework, thus leaving room for absolute randomness, where the spectacle of the sequence is given priority over everything else. Therefore, a BASE-jumper can just jump into the intersection out of nowhere, just like in the fantasy of two motorcycle jumpers in the desert hitching a ride in a souped-up Audi driven by Pink, who takes them to the snow-capped mountain peaks. In the end, it’s all the more regrettable that the only limitation on Bogner’s imagination is the default IMAX format, or rather the size and inoperability of the IMAX camera. On the other hand, Bogner had already reached his peaks anyway, so there is nothing wrong with the fact that he conceived his final work as a purely technological vanity project. So what are the absolute highlights of Bogner’s filmography? White Magic is his most breathtaking achievement (both in terms of the challenges of execution and the breakneck action sequences and individual sporting feats); Fire, Ice and Dynamite is the most entertaining symbiosis of conventional narrative and Bogner’s vulgar cinema of attractions. Stehaufmädchen is the most playful, spontaneous and rebellious middle finger raised to all contemporary norms and the rest of Bogner’s later works.

Ski into the Sun (1997)

In the interest of the bombastic audio-visual promotion of Bogner’s 1997 winter collection, Willy Bogner cut together a downright hopeless, music-video-style rehash in which he newly executed various spectacular concepts and adrenaline-fuelled action feats from his previous works. As a repeat of things already seen, however, this medium-length short isn’t as impressive as the self-taught master’s top projects, but the playlist of slow-motion money shots is still simply nice to watch.

Avaria no asfalto (1997)

Whereas in its time Breakdown was seen by many people as just another run-of-the-mill “American” movie, the merits of this precisely constructed thriller have become more apparent with the passage of time. Unlike those truly mediocre flicks that haven’t stood the test of time (such as Joshua Tree with Lundgren, which has a similar plot), Mostow's desert movie still works well. This is due to the overarching tendency toward simplicity, which is reflected not only in the individual twists, and especially to the concept of the central protagonist, who combines the best of the tenacious, masculine heroes along the lines of John McClane with ordinary, witty, likeable guys dealing with situations on the fly in the manner of Richard Kimble in The Fugitive. Kurt Russell perfectly embodies this duality by showing all of the aspects of an unnerved character in his acting. In addition to that, he performs most of the action feats himself, which aids the believability of the individual sequences. Despite all of that, however, Breakdown still remains sufficiently formulaic that it works as a standard genre movie with all of its attractions and delights. It’s also pleasing due to the various minor yet adequate deviations that make it more than just an average spectacle with well-built suspense.

Pleasantville (1998)

In the better case, every epoch carries with it the belief that it is more highly developed and advanced than those that came before it. Today, nearly a quarter century later, it can thus be instructively entertaining to watch Pleasantville, in which the supposedly free and progressive lens of the 1990s is used to view the fictional ideal of 1950s America, or rather a fictional version in the form of a stylised sitcom from the period. In its individual moments, Pleasantville still remains tremendously fascinating and entertaining, but also breathtaking and touching, as a proper melodrama should be. Despite that, however, the meta-illusion of how a plain girl and a proper nerd bring emancipation and progress to an absurdly conservative series is disrupted by nagging thoughts regarding the degree of naïveté and intrinsic limitations of the nineties perspective. On the other hand, it places a mirror in front of our own supposed enlightenment, which in turn will seem ridiculously half-baked to future generations. Nevertheless, Pleasantville has lost none of its pioneering nature at the technical level. It is part of an unfortunately small group of projects (such as Forrest Gump) in which computer tricks were not a crutch or a cheap attraction, but a creative tool for creating fascinating functional illusions.

Raising Cain (1992)

In its official version, Raising Cain offers an imperfectly constructed yet superbly directed paraphrase of Psycho. Many of the ills that plague the version released to cinemas are remedied by the fan-made “director's cut”, which was based on the original screenplay and enthusiastically endorsed by the director himself. In both versions, however, it is not only John Lithgow’s delightfully deranged performance that stands out, but also the almost fetishistic directing. De Palma thoroughly enjoys staging spectacularly artificial but ingeniously layered scenes that come across as tableaux vivants in which kitschy surrealism is combined with exaggerated drama.

Noite Violenta (2022)

In the golden age of Hong Kong cinema, when several dozen action films vied for viewers’ attention every year, the rule was that the way to distinguish one’s film from those of the competition was to include previously unseen attractions, or at least a unique screenplay, setting and overall visual or subgenre stylization. The filmmakers from 87North Productions consciously follow the Hong Kong tradition in many respects. Unfortunately, however, over the four years since they stopped being mere subcontractors providing choreography for action scenes and started producing movies themselves, they have reached a point where, instead of amazement and excitement, their films evoke only a superficially altered impression of something that has already been seen. This was inevitable, because unlike in the case of the major productions from the golden age of Hong Kong cinema, they have nowhere to grow. On the one hand, they have no competition, but no one will entrust them with bigger budgets that would enable them to further develop. Furthermore, they don’t have any stars other than Keanu Reeves who would devote themselves to the action genre, work on themselves and continually impress viewers with new stunts. On the other hand, it didn’t matter that Nobody is a variation on John Wick, because the film was carried by the excellent Bob Odenkirk. The same was true of Kate in relation to Atomic Blonde thanks to Mary Elizabeth Winstead and the pop-Japanese stylisation. Not to mention that in both of these cases the choreography worked with real physical aspects and a specific setting. But Violent Night not only comes across in its choreography as a derivative of the same company’s previous films, but the thing that is supposed to make it different is in itself derivative. The whole film blatantly paraphrases Home Alone and Die Hard, this time with Santa Claus himself battling the highly capable bad guys. Unfortunately, in practice this is all reduced to the insipid juvenile attraction of Santa cursing with a broken nose and a blood-soaked beard through most of the film. Of course, he also uses Christmas items like tree ornaments to eliminate his enemies. However, the film peculiarly comes most alive when it dispenses with the would-be shocking of American viewers stupefied by the illusion of Christmas and moves to the attic in the manner of Home Alone and to the tool shed in the style of Commando. But even these flashes of inventiveness (though still derivative) cannot obscure the desperate fact that David Harbour doesn’t have the charisma to carry an entire film on his own and that Tommy Wirkola is a master of gimmick movies whose final execution falls far short of the promise of their catchy concepts.